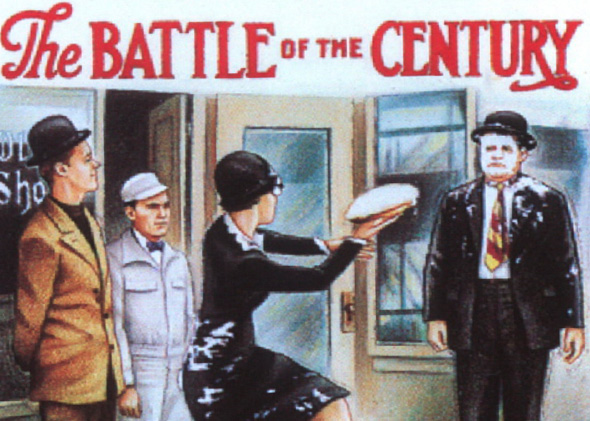

A Laurel and Hardy reel thought lost for decades is discovered.

Courtesy of Hal Roach Studios

Over the weekend, it was quietly announced at the Library of Congress' festival of "unidentified, underidentified, or misidentified films" that one of the most deeply mourned lost treasures in film history has reappeared. As reported by Pamela Hutchinson at Silent London, silent film historian Jon Mirsalis unexpectedly rediscovered the second reel of Laurel and Hardy's 1927 film The Battle of the Century, lost for 60 years. The Battle of the Century is not only a crucial film in the careers of Laurel and Hardy, but it contains the biggest, best, funniest execution of the pie-in-the-face gag in cinematic history. For fans of early film comedy, this discovery is roughly the equivalent of Moby Dick swimming ashore carrying the Holy Grail.

Film historian Anthony Balducci has traced pie throwing on film back to at least 1905, but the Keystone Studios, remembered today for its eponymous cops, ran the bit into the ground in the 1910s. When Buster Keaton started making his own features in 1923, he explained in his autobiography, he forbade pie jokes entirely. But four years later, in September 1927, a virtual unknown named Stan Laurel proposed to revive the gag-by making it bigger than it had ever been before.

Both Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy had been appearing in films throughout the 1920s, occasionally together, but had only been officially paired together since that June. Although they'd shot the first three Laurel and Hardy films, none had yet been released. Nobody at the Hal Roach Studios knew it at the time, but they were at the center of a unique confluence of cinematic talent: not just Laurel and Hardy, but directorial legends Leo McCarey, George Stevens, and Clyde Bruckman. McCarey and Stevens had their greatest successes ahead of them; Bruckman, the most successful of the group in 1927, hadn't yet begun his spectacular implosion. The first reel of the new feature seemed like a surefire hit: a parody of the Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney "Long Count Fight," which had just happened in September of 1927. No one had any particular reason to believe Laurel could pull off the tired pie throws he planned for the second reel. But he had an improvement in mind, as Philip K. Scheuer explained in a Los Angeles Times profile two years later: "His method would consist, simply and directly, of throwing more pies. Not one, not two, not ten or twenty, but hundreds, even thousands."

It took some political infighting, but Laurel eventually sold Hal Roach on the idea. The studio bought an entire day's output of the Los Angeles Pie Co. and, that October director Bruckman staged the greatest pie fight in history: 3,000 pies soaring gloriously through the air. And yet the secret of the film's success, as Laurel told Scheuer, turned out to be not volume, but pacing.

The Battle of the Century opened in December of 1927 and for a few happy months could be seen in theaters, randomly paired with anything from Lillian Gish's "throbbing drama of love and sacrifice" The Enemy at the Hippodrome in Murphysboro, Illinois, to Henri Fescourt's 1925 adaptation of Les Misérables-original running time 359 minutes-at the Bentley Theatre in Monongahela, Pennsylvania. In those days, when films left theaters, they were done: no revival screenings, no television, just a pile of prints melted down to recover the base metals. The last theatrical screenings happened in the summer of 1928, at the kinds of second-rate theaters that pointedly didn't advertise air conditioning. Audiences who braved the heat were, with a vanishing few exceptions, the last to see The Battle of the Century in its entirety.