“Some cases, like this one, kind of creep up on you on their hands and knees and the first thing you know, you’re in it up to your neck.”

Film noir liked to play with first-person perspective in the 1940s. Audiences were dropped into Dick Powell’s worn shoes in Murder, My Sweet (1944), while Humphrey Bogart spent the first act of Dark Passage (1947) hiding behind the camera. Given the relative success of these films, it was only a matter of time before someone attempted to tell an entire story using first-person perspective.

Enter Lady in the Lake.

MGM was taking a big risk, given that they were using a hugely popular character, Philip Marlowe, and an actor known primarily for his good looks, Robert Montgomery. The mishandling of either could lead to financial suicide at the box office. Still, producer George Haight and Montgomery (who also directs) went forth with their creative gamble, and the results were… intriguing, to say the least.

The film’s gimmick-promoting poster.

The film’s gimmick-promoting poster.

Even before the gimmickry comes into play, its clear that this is not the traditional Philip Marlowe. Montgomery takes a more stern approach to the character, doing away with the charm and wit of part incarnations. His Marlowes is a stone-cold businessman, cunning as he is disrespectful. Even when making humorless remarks, Montgomery plays it sans joy– not a bad thing, necessarily, just different.

Montgomery takes a looser, more energetic approach behind the camera. The opening credits establish a tone of Christmas postcards and holiday cheer. The punchline, of course, is the reveal of a handgun, assuring us that we’re in for the usual detective fodder. Montgomery sits at a desk and speaks to the audience, informing them of what to expect over the next 105 minutes. Lake scatters these fourth-wall interludes throughout, and truth be told, they’re pretty enjoyable. It’s here that the film makes good on its tagline: “YOU and Robert Montgomery solve a murder mystery together!”

“I like your tan. That’s very Christmassy.”

“I like your tan. That’s very Christmassy.”

The film finds Marlowe working for magazine editor Adrienne Fromsett (Audrey Totter). She wants him to locate the missing wife of her boss Mr. Kingsby (Leon Ames), but, as is the case with all Raymond Chandler novels, it gets way more complicated than that. Bodies start turning up, police start acting funny, and Marlowe is left to make sense of it, all while romancing the manipulative Fromsett.

Totter is given the trickiest stuff to play here. Nearly all of her scenes are with Montgomery who, while convincingly tough, doesn’t offer much in terms of emotion. As a result, most of Totter’s temper tantrums or seductive glances– fun as they may be– feel hollow. The novel’s patented zingers remain intact (“When it comes to women, does anybody really want the facts?”), but the scenes lack chemistry due to their unorthodox setup. Truth be told, the only actor who sticks the landing is Jayne Meadows, whose jittery wasp of a character repeatedly outshines Marlowe.

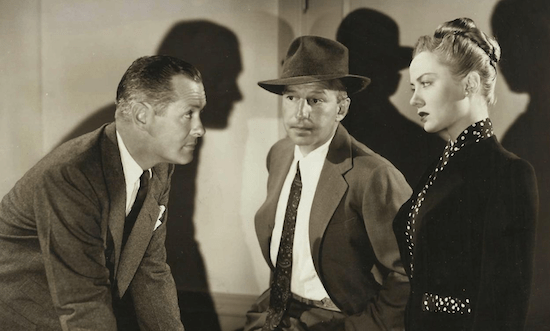

A rare sighting of Marlowe’s face.

A rare sighting of Marlowe’s face.

Essentially, therein lies the problem with Lady In The Lake. Upon release, The New York Times commended Montgomery’s ability to wield the camera, but made a point of explaining what went wrong:

“In making the camera an active participant, rather than an off-side reporter, Mr. Montgomery has, however, failed to exploit the full possibilities suggested by this unusual technique. For after a few minutes of seeing a hand reaching toward a door knob, or lighting a cigarette or lifting a glass, or a door moving toward you as though it might come right out of the screen the novelty begins to wear thin.”

To MGM’s credit, they managed to turn Lake into a box office hit– claiming it would be the first of its kind and the most revolutionary style of film since the introduction of the talkies. They were clearly overstating the film’s importance, but at that time, the emphasis on gimmickry worked. After Lady in the Lake, films started to indulge things like 3D and Smell-O-Vision. While not as painfully dated as those ventures (Hardcore Henry did the same thing in 2016), it does suffer from similar creative shortcomings.

It isn’t a classic Philip Marlowe adaptation, nor is it a classic film noir. But to its credit, Lady in the Lake is still a lot of fun to watch. Montgomery’s directorial debut is an exercise in audacity, and on those merits, if those merits alone, its worth revisiting. C

TRIVIA: For the unseen role of Chrystal Kingsby, the credited actress was Ellay Mort. As it turns out, no such person existed, and was a phonetic joke from the French phrase “elle este morte” meaning “she is dead.”

–Danilo Castro for Classic Movie Hub

Danilo Castro is a film noir specialist and Contributing Writer for Classic Movie Hub. You can read more of Danilo’s articles and reviews at the Film Noir Archive, or you can follow Danilo on Twitter @DaniloSCastro.

I’m a big fan of Raymond Chandler but I haven’t seen either Murder My Sweet or The Lady in the Lake, a problem I will remedy at the first opportunity. Having read his novels so many times I sometimes have problems when things are changed for the film. version, but both of these look interesting enough to help me get past that. Excellent review, thanks.

Pingback: Silver Screen Standards: Tension (1949) | Classic Movie Hub Blog